Environmental Urban Planning: An Integrated Planning Framework

Written By:

Farah Kassab, Urban Planning Expert

Nivine Issa, Managing Director, Terra Nexus

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization and global population growth has posed significant pressure on infrastructure causing a myriad of problems around quality of life and environmental pollution. Urban spaces, when not properly planned, may struggle to adapt to the ever-evolving challenges of population growth, climate change impacts, and degradation of natural resources. To attain sustainable development, urban spaces must be planned and operated to form a balance between human needs and the natural environment, utilizing resources in a way to meet the needs of the present without compromising the needs of the future.

In recent years, there has been a revived global focus on environmental sustainability across various industries. The Middle East region, in particular, is in a transformative state, undergoing major development. With several new projects hailed as new benchmarks for sustainable and environmentally conscious design globally, yet many existing developments still do not meet the mark for resilient and sustainable communities.

The region has long established the protection of the environment and sustainable development as part of its planning mandate within its regulatory bodies. This included developing locally adopted frameworks and guidelines based on globally recognized green building rating systems such as BREEAM and LEED.

The integrated planning approach recognizes that cities are intricate systems with multiple dimensions and layers which include policy, regulations, land use planning, infrastructure & transportation, economy, environment and stakeholder engagement. It aims to create sustainable, resilient and inclusive cities by incorporating these in the decision-making process. The exponential pace of development, supply chain shortages and limited supply of expertise in the region may challenge the ability to fulfill the aspirations of the integrated urban planning process across mainstream projects.

While sustainability frameworks have been well established and adopted globally, an environmental urban planning framework is not explicitly defined in a typical urban planning process.

This article defines a comprehensive environmental urban planning framework that integrates environmental factors across every stage of the planning process. The intent is to bridge the gap between urban and environmental planning methodologies in the aim to tangibly influence developments through environmentally conscious design.

2. Typical Urban Planning Work Plan

Master Planning projects are typically lead by a Lead Masterplanning consultant who will establish a workplan along the following 5 stages*:

- Stage 0: Business Plan and Vision

- Stage 1: Data Collection & Analysis

- Stage 2: Pre-Concept Masterplan

- Stage 3: Concept Masterplan

- Stage 4: Detailed Masterplan

*Stages may vary based on client scope, some components such as Business Plan and Pre-concept may be commissioned separately.

Typical of the fast-track nature of projects in the Middle East, several tasks are planned to run in parallel across these stages. For instance, environmental surveys initiated in the Data Collection & Analysis stage may require more time and extend through the Pre-Concept optioneering and Concept stages. This means the integration of environmental studies occurs at a far later stage in the planning project timeline. Consequently, the environmental team/specialist works in a vacuum and misses the opportunity to explore and develop a tailored environmental strategy alongside the masterplan design development.

In an ideal scenario, the Client would have commissioned the environmental investigations prior to awarding the masterplan and dictated the environmental integration as a requirement from the start.

More often than not, ‘environment’ as a discipline is conflated with the idea of conservation only, whereas environmental planning is driven by the concept of “Building with Nature”. In other words, it aims to achieve urban development goals while maintaining the integrity of the environment.

3. What is Environmental Planning?

Environmental design and planning is a multidisciplinary field that involves the strategic and systematic management of social, economic, and environmental factors. It aims to minimize impact and maximize benefits between human activities and the environment.

Like Urban Planning, Environmental Planning also operates on a set of principles and guidelines as follows:

- Biodiversity Conservation and Enhancement: A fundamental principle to environmental planning is to protect and enhance biodiversity on a given project. It involves active efforts in the form of investigative studies and purpose-driven designs not just to preserve natural habitats but to support the enhancement of existing ecosystems.

- Pollution Prevention: The prevention and reduction of pollution are core principles focused on minimizing the release of harmful substances and the general disturbance of the surrounding environment.

- Resource Efficiency: A core principle of sustainable development and environmental planning is the sustainable use of existing resources, the reduction of waste, and the minimization of resource consumption.

- Resilience and adaptation to climate change: An essential aspect of future-proofing a development is ensuring its resilience and capacity to adapt to climate change. These design and operational practices prepare communities and ecosystems for the challenges a changing climate would pose.

- Cultural heritage preservation & revival: A key component of environmental planning is preserving local heritage and cultural value within and around a given project. This is particularly important when working with local communities.

So how does this fit into the urban planning work plan? And how can we make sure these principles are seen through into the final product?

4. The Path to an Urban-Environmental Planning Framework

A. Fragmented Environmental Initiatives: A Call for Coordinated Action

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) have become commonly used in assessing environmental impacts of developments on surrounding communities. In addition, a considerable number of countries around the world have taken into account sustainability principles and practices in their city planning efforts. Cities are actively developing guidelines for sustainable development addressing the need for Low Impact Development, Climate Change Adaptation, Emergency and Crisis Response and Sustainable Communities.

Furthermore, other international institutions have initiated the Sustainable Cities Program (UNEP and UN-Habitat), Localizing Agenda 21 (UN-Habitat) as well as several bilaterally funded programs (e.g. Danida’s Green Cities programme). While the efforts in the sustainable development community have been substantial in recent years, they remain fragmented and uncoordinated.

While a number of global institutions are now calling for an integrated urban planning process, at the time of writing this article, a globally recognized environmental urban planning framework that project teams can easily adopt has not been developed. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) in collaboration with the Cities Alliance and International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), recognize how important this is, stating: “The most effective strategies for integrating the environment in urban planning and development involve incorporating the environment in existing tools rather than developing stand-alone approaches” (UNEP, 2013).

So how can we bring together two historically siloed disciplines into a structured urban planning framework? This can be achieved by:

- Defining the seven key environmental aspects influencing urban development.

- Aligning environmental methodologies across typical urban planning stages.

- Capturing the inter-disciplinary touchpoints at every design stage.

These three steps are further explained below.

B. Environmental Planning Perspectives: The Seven Key Aspects Shaping Urban Development

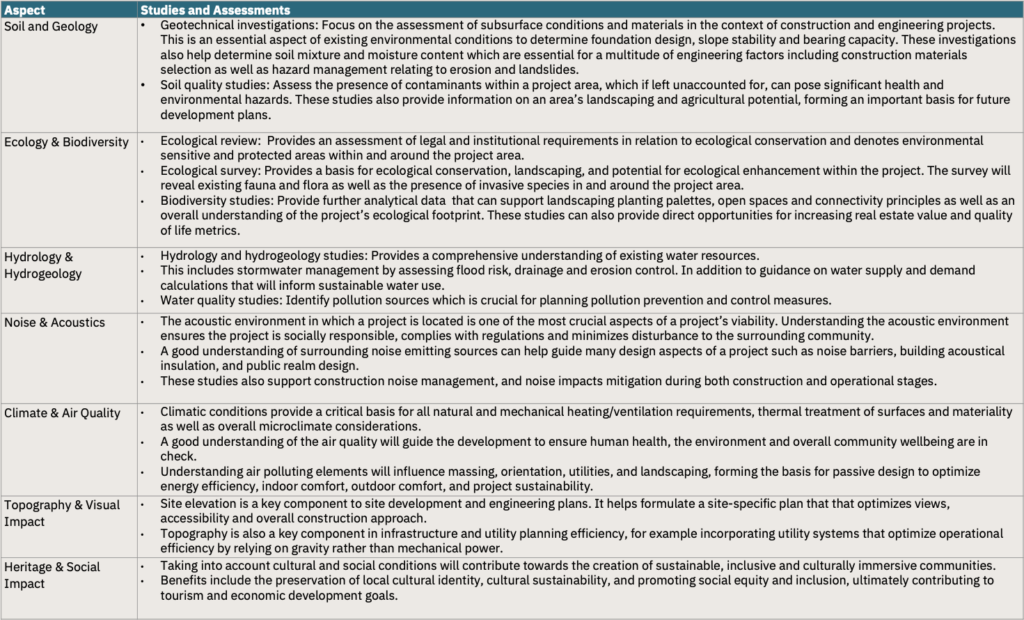

There are seven key environmental aspects that can inform different elements of the masterplan. These are described in the table below:

C. Proposed Framework: Environmental Urban Planning and Development

During the design development process, the teams aim to develop sustainable and resilient communities that strike a balance between human needs, natural systems, and the built environment. The integrated approach, presented in the following sections, bridges the gap between the planning components and the environmental principles sought by the respective specialists.

In typical scenarios, environmental deliverables are submitted independently from design reports, often to environmental authorities. As such, we rarely see these environmental outputs being discussed within design workshops.

It is important to have the planning and environmental teams working in a synchronised manner for the reasons below:

- Holistic approach: Urban planning and environmental considerations are deeply interconnected. Urban planners focus on shaping the physical layout of cities, considering aspects like land use, transportation, and infrastructure. Meanwhile, environmental experts assess the impact of human activities on natural ecosystems and resources. Combining these specialist areas ensures a holistic approach to development, where environmental concerns are embedded into urban plans from the outset.

- Sustainable Development: Integrating urban planning and environmental expertise enables the pursuit of sustainable development goals. By considering environmental factors such as biodiversity, air and water quality, and carbon emissions alongside urban planning decisions, design teams can create cities that minimize their ecological footprint and promote long-term environmental health.

- Policy Alignment: Prioritising and establishing actionable policies from planning to operations. When planning and environmental teams are more deliberate in aligning planning and design decisions, the permitting process is streamlined and more likely to successfully comply with environmental regulations and sustainability standards.

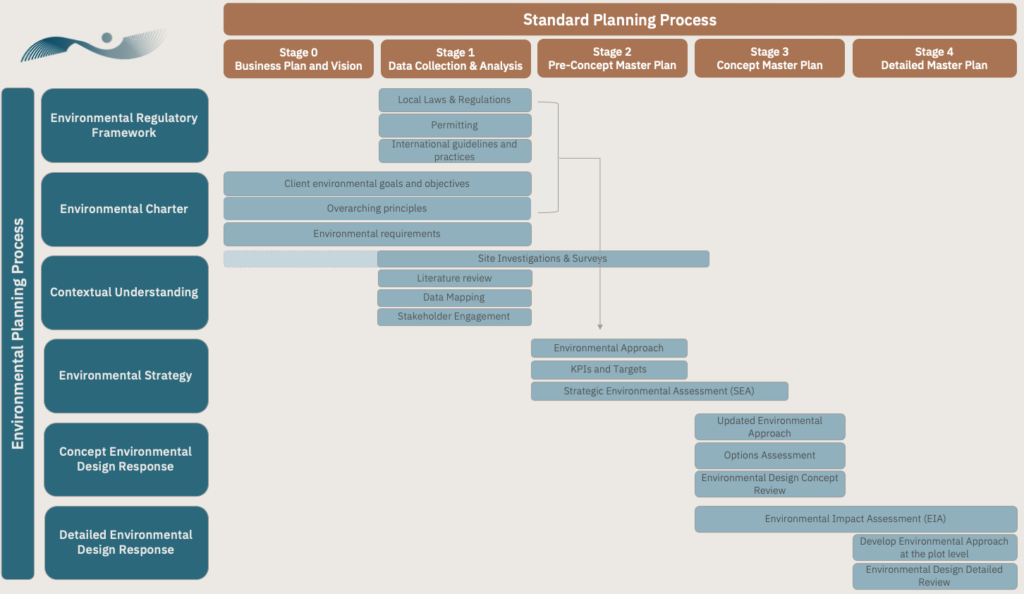

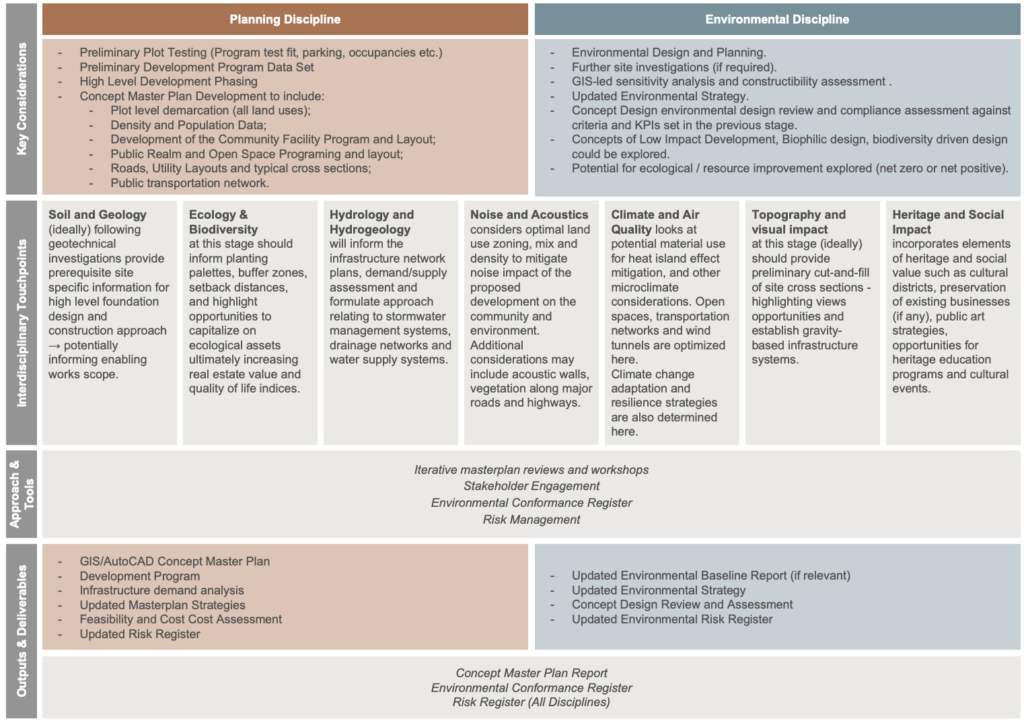

The below matrix illustrates the integration of environmental deliverables and contributions into the typical masterplan development process. This serves as a roadmap for planning and environmental disciplines to navigate and improve the integrated design development process.

We later take a deeper dive into how the different environmental processes and inputs may shape urban planning decisions geared towards cities that are sustainable, resilient, and conducive to the well-being of their inhabitants.

Figure A: Integrated Urban-Environmental Planning Diagram

The matrix above maps out the six key environmental deliverables and their detailed outputs against the five stages of a standard planning process. We further explain how these feed into each design stage below.

D. Process Touchpoints: Environmental interfaces across each of the urban planning stages

Taking the urban planning design stages as a structuring framework, with exception of Stage 0, we have mapped out the following aspects for each master planning stage to assist teams in following a structured approach:

- Key considerations – Showcases the focus areas by each team ,

- Interdisciplinary touch points – Illustrates how the 7 key environmental aspects influence planning decisions,

- Outputs – Typical scope outputs for each discipline, and

- Deliverables – Typical scope deliverables.

These are illustrated for both disciplines side by side to enable clarity and dialogue between the two disciplines’ workflows.

a. Stage 0: Business Plan and Vision

With reference to Figure A above, we have included a Stage 0 that refers to the project visioning and overall brief. This is typically undertaken by the client prior to commissioning the master planning works. Though limited, we have observed specific instances where the client is interested in addressing the environmental aspects as part of the business plan vision. In such cases, the client may have initiated preliminary site surveys. This would be ideal for the consultant who will be engaged, enabling the integration of the environmental aspects early in the planning process.

b. Stage 1: Data Collection and Analysis

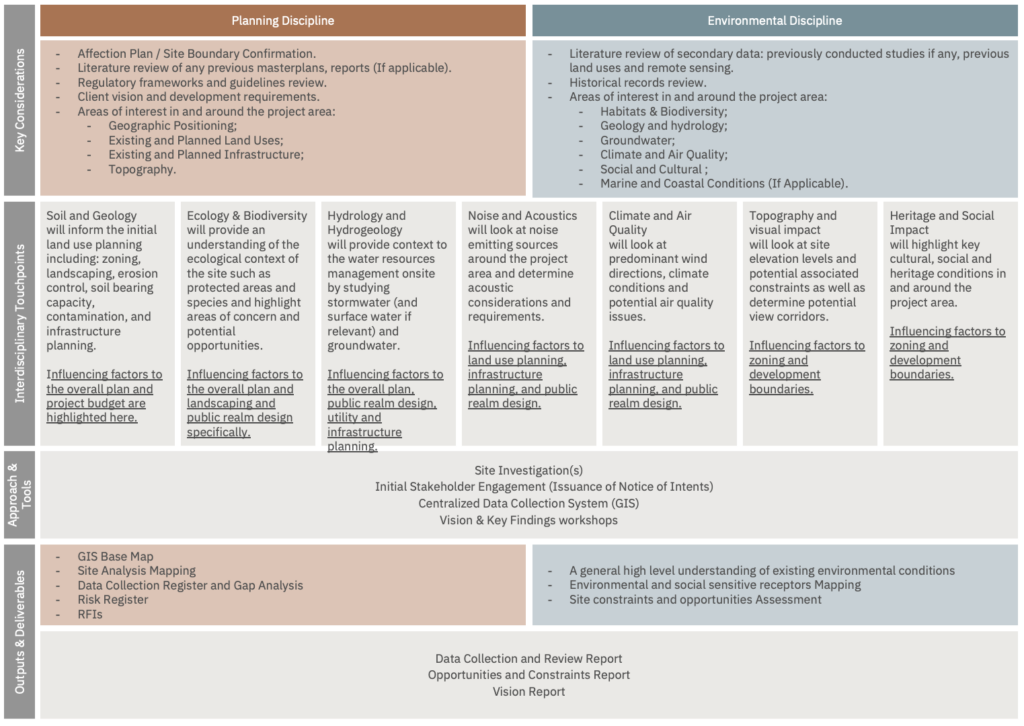

Data collection and analysis serves as the foundation for evidence-based decision-making in sustainable development, and the creation of liveable and resilient cities.

During this stage, the urban planning team assesses the demographic requirements, spatial aspects of the site which include site boundary, land use and infrastructure taking into consideration both existing and planned developments. On the other hand, the environmental team maps out key environmental site features such as habitats and biodiversity, climate and air quality, geology, and hydrology as well as social and cultural conditions.

Some aspects that environmental and urban planning teams should jointly touch on:

- Key drivers associated with the client vision and project brief such as liveability, wellbeing etc. and how environmental considerations will be instrumental in achieving these.

- Environmental site constraints and opportunities

- Urban systems assessment and sensitive receptors

- Existing environmental policies and legislation and their spatial/planning implications on the urban framework

The table below further illustrates the key aspects planning and environmental teams typically work on, their approach and their individual and combined outputs and deliverables. During this stage, the teams jointly acknowledge the interdisciplinary touchpoints that may potentially influence the masterplan in the coming design stages.

Figure B: Stage 1 Data Collection & Analysis

Let’s consider the following touch point: Existing soil and geology condition. As an example, the study may indicate potential concerns in soil conditions that may require rehabilitation or reinforcement. Such information is valuable in the way it informs land use planning, including zoning, landscaping, erosion control, soil-bearing capacity, contamination, and infrastructure planning. These requirements will influence key planning decisions and may require reconsideration of the client’s original project budget.

Key to optimizing this iterative interdisciplinary planning process is to centralize collated site data into an integrated data collection system (GIS) to process multi-layered datasets. Furthermore, and within a week or two into this stage, it is vital that at least one coordination workshop is conducted to discuss the following:

- Environmental constraints and opportunities

- Key environmental selling points that impact overall human experience such as liveability and wellbeing

- Potential strategies and approaches that capitalize on existing environmental features and overcome key environmental challenges.

- Benchmarks from other projects locally, regionally, and globally to address these.

Finally, impactful environmental site features should appear in all base maps throughout the data collection stage deliverables, rather than them appearing in the environmental chapters only.

C. Stage 2: Pre-Concept Masterplan

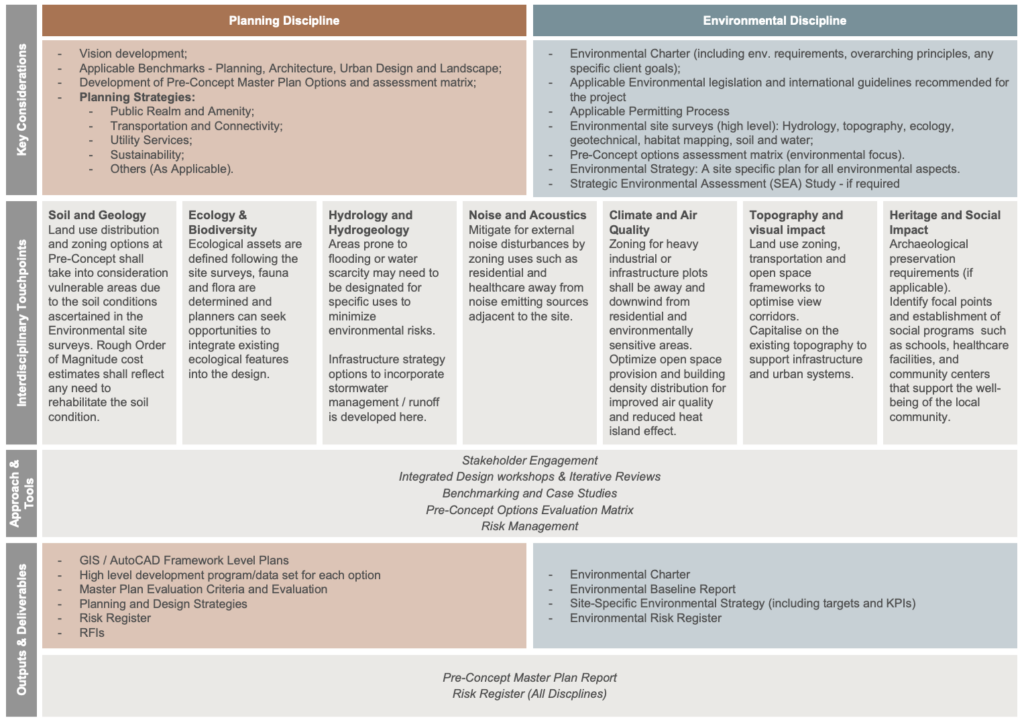

This stage is mainly concerned with setting the vision and the exploration of the various strategies that will inform the master plan development in conjunction with the outputs of the studies conducted in the previous stage. The below tabulates the considerations, interdisciplinary touchpoints and tools that can be used to facilitate the integrated planning process during this stage.

Figure C: Stage 2 Pre-Concept Masterplan

Continuing with the touchpoint discussed earlier, soil and geological conditions, at this stage, the environmental team will undertake further surveys on site to provide further assessment of the current conditions, and, geotechnical investigations as well.

“As an example, suppose the team identifies vulnerable soil conditions in significant part of the site.

The planning team may present two options:

- Option A – Enables maximum use of the site for development and thus require investment into improving the soil conditions.

- Option B – Proposes alternative uses that are suitable for this vulnerable area, resulting in less development and less investment in the soil management in the subject zone and increase the density of development in another area in order to reach the total program target.

As per standard procedures, options are evaluated against a number of factors. The urban environmental framework encourages the integration of environmental criteria into the evaluation matrix.

Using the inter-disciplinary touchpoints as a guide, the discussion on the design table may look something like this:

“For instance, in the case of Option A, how does undertaking extensive works impact any identified ecological assets? How would a less dense and more expanded plan influence climate, air quality and visual impact?

In the case of Option B, will additional density result in acoustic and noise issues that require further mitigation? In the same vein, will the development require mitigation for light pollution for any adjacent ecological areas? What are the impacts on cost and air quality given the compact infrastructure required, would there be any social benefits associated?”

This should be done prior to the client progress workshop(s) to ensure the optioneering exercise and the evaluation matrix incorporates all specific environmental considerations. Furthermore, key environmental components posing risks on the development of the urban framework should be added and maintained in the risk register.

To ensure the effectiveness of the optioneering exercise, an integrated data collection system (GIS) will be a vital tool to visualize and quantify the proposed options and their impacts. As such, this stage ought to be the most dynamic, focussing on stakeholder engagement between the various disciplines, client team and should extend to external agents and authorities (as applicable).

This stage also involves engagement with relevant authorities to determine the relevant permitting procedures and in particular the requirement for a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) or Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Common practice in the development of an urban planning framework for a project of a particular scale is the development of a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). This is not a robustly governed process in the region yet but has increasingly been adopted in recent years. An SEA is a systematic and comprehensive process used to evaluate the environmental effects of proposed policies, plans and programs during their development stages, and this is typically done during the pre-concept masterplan stage where options are still being explored.

It is worth noting that the SEA typically happens in parallel with the design development, preferably by a third-party environmental consultant. This does not refute the necessity for environmental urban planning process to take place by an integrated multidisciplinary team of experts.

The interaction between the disciplines using the various tools presented above (The SEA, evaluation matrix, environmental risk registers etc.) will support in evaluating and identifying the preferred option. The process may require revisiting along the way the goals and priorities to ensure alignment across all stakeholders. At the same time, the process encourages extending the discussion into the relevant strategies, benchmarks and practices. This will address the interplay of environmental, social and economic concerns in the Concept Master Plan development stage to follow.

D. Stage 3: Concept Master Plan

The Concept Masterplan is a more refined stage where the initial ideas and options explored at the Pre-Concept stage are synthesized into a coherent vision. Having established the overall vision, goals, and key design principles in the former stage, the spatial organization and character of the development start to take shape. This is an iterative process which includes multiple rounds of design, technical and financial studies aimed at striking the balance between the various project goals and priorities.

It is important to recognise that the Concept Master Plan establishes the major moves, such as land use and population distribution, infrastructure and transportation corridors and public realm network and associated design strategies. In addition, the project budget is will be refined along with the masterplan development. During this time, the environmental team is conducting further site investigations and assessing site sensitivities through the establishment of an EIA. An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a systematic process used to identify, predict, assess and mitigate the environmental impacts of a proposed project. This allows for potential environmental issues to be identified and addressed with the appropriate strategies before significant resources are invested in the development of a specific plan, reducing the likelihood of negative environmental impacts and improving the overall sustainability of the master plan. Essentially the EIA feeds into the design appraisal of the evolving Concept plan. As such, it is important to involve a member of the environmental design team in the internal design workshops and attain updates on the environmental investigations as they emerge to incorporate in the master plan and strategy as applicable.

Figure D: Concept Master Plan

“There will be instances where the interdisciplinary touch points require an update in the environmental approach and strategy rather than simply impose structural/spatial restrictions on the masterplan structure. This includes introducing measures in the detailed design or operations that will result in environmental improvement measures. Alternatively, the team may explore innovative and sustainable development strategies such as Low Impact Development (LID) and Biodiversity driven design and integrate these in the masterplan layout and design strategies that will be take shape in the detailed stage. For example, Low Impact Development (LID) strategies from the environmental perspective would influence the planning team’s design of the open space network whereby the open space layout out and programming becomes part of green infrastructure system to manage stormwater runoff. Alternatively, this may influence the infrastructure strategy that opts for a decentralized stormwater management system that mimics natural hydrological processes instead of a centralised system that would have a significant spatial impact on the plan (Hydrology and Hydrogeology touchpoint)”.

Different solutions such as the above will have varying financial implications that can be presented to the client. It is worth making the distinction between short term and long-term financial impacts which would also influence the operational sustainability of the project.

How can we ensure this integrated process takes place at this stage and allow the teams to organise and track these additional considerations more deliberately?

To help bring this all together, planning and environmental teams can jointly develop an Environmental Conformance Register. This is a project specific matrix that outlines all environmental aspects with reference to how the masterplan addresses them at the Concept Stage. This will enhance the success of the project in terms of maximising environmental benefits, enhance coordination and set clear roles and responsibilities from the start. As such, this is a live document that will continue to inform the detailed master plan stage and more importantly be part of the handover for further implementation and construction phases.

The efforts are then culminated in the development of the CMP Report which provides the following:

- An integrated and coordinated concept masterplan design that has incorporated key environmental aspects and integrated fundamental sustainable development options

- Preliminary Land use, Roads and Utilities layouts

- A Preliminary Development Program and cost assessment

- An environmental Risk Register

- An Environmental conformance register demonstrating compliance with project’s environmental strategy and client brief.

Following this approach, the concept masterplan would have been built on a robust foundation that adequately combines urban and environmental planning principles and would form the basis for subsequent phases of the planning and design process.

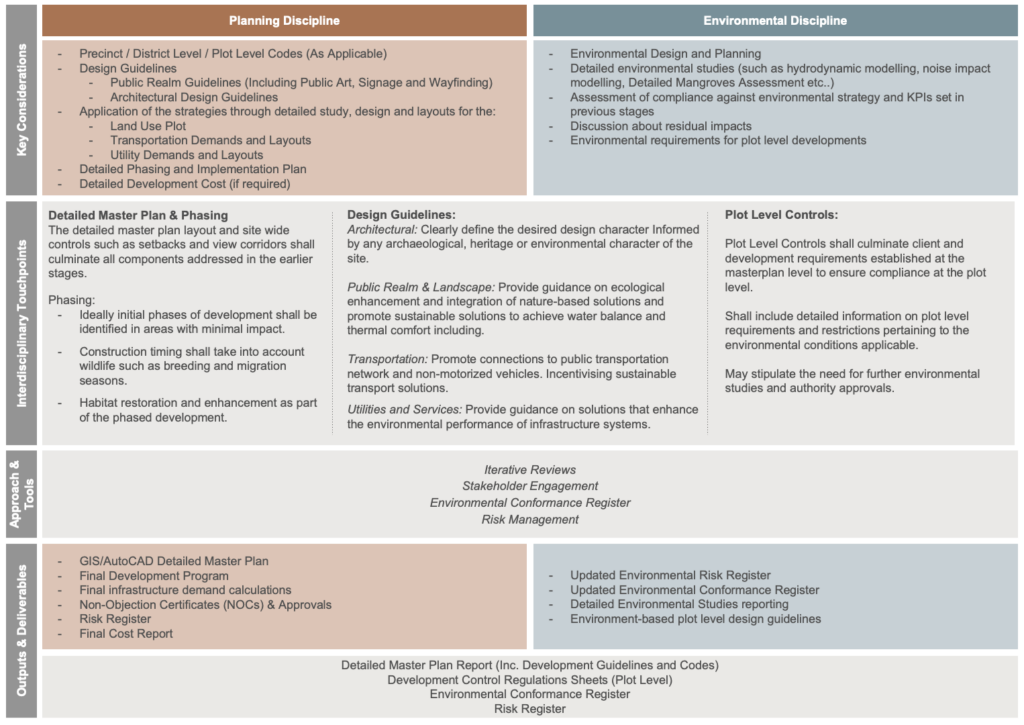

E. Stage 4: Detailed Master Plan

The Detailed Master Plan stage involves the comprehensive elaboration and refinement of the initial conceptual framework, specifying precise design details, zoning regulations, infrastructure layouts incorporating the environmental considerations agreed upon in the Concept Master Plan stage.

If the proposed framework is followed by which the environmental assessment and considerations are dynamically integrated into the design process, accordingly, these considerations will culminate in at the master plan site-wide and plot-level considerations such as setbacks, green and visual corridors as well as the phasing.

Figure E: Detailed Master Plan

The Design Controls and Guidelines at the plot level reflect the client requirement and site conditions. This is the team’s opportunity to build upon the strategies and environmental led solutions that would have emerged as part of the previous stages discussions and EIA study.

Depending on the agreed upon strategies, these will determine the difference between what should be established as a guide or regulation to be strictly followed by those undertaking the design development and implementation. For example, development guidelines may introduce opportunities for ecological enhancement of a specific zone which includes a design intervention, while controls would put specific measures on the technical specifications of that specific intervention.

Depending on the project scale, it would also be appropriate to stipulate additional environmental studies for applicable plots that will further inform the final technical controls. With reference to implementation, phasing of construction is also an important aspect in managing environmental impact, this can be achieved by considering the following aspects:

- Initiating developments in areas with minimal impact and gradually progressing to more sensitive areas.

- Defining the construction timing: Avoid critical times for wildlife such as nesting seasons for birds.

- Incorporating habitat restoration and enhancement measures as part of the phased development.

The resultant DMP Report will integrate and conclude all the combined environmental and planning studies to date as per the following:

- An integrated and coordinated detailed masterplan design that has incorporated key environmental aspects and sustainable development in the final programme density distribution and site wide level controls.

- Transportation and Utilities systems reflecting the final agreed strategies in terms of final utility plot distribution, utility corridor networks that will facilitate application of passive, green or automated technologies in the infrastructure design stages to follow post the master plan stage.

- Final development program and cost assessment that incorporates the capital costs for any key environmental solutions.

- Closure of environmental risk register for the master planning stage.

- Closure of environmental conformance register demonstrating compliance with project’s environmental strategy and client brief.

Finally, across all the DMP deliverables, the team members from the planning and environmental disciplines shall close out the risk register and the conformance register. This is an essential step in the close out and handover process. It also reinforces the Quality Assurance and Quality Control measures for the project.

5. Conclusions

Numerous institutions and frameworks have recognized the importance of implementing an integrated design development process, within the realm of urban planning. Often, and on projects in the ME region, environmental teams work in isolation. Unfortunately, this approach often results in missed opportunities to incorporate critical environmental considerations into the design. Consequently, the potential advantages of a cohesive design approach, which could bring about significant economic, environmental, and social value, are frequently overlooked.

The aim of the framework outlined in this paper is to integrate environmental planning seamlessly into an already established planning process. The aspects and touchpoints emphasized should not be viewed as an exhaustive list of all project elements; rather, they serve as a framework to guide the development of a site- and project-specific approach to the environmental-urban planning process.

It is crucial to clarify that we are not introducing an additional discipline or a distinct deliverable that the client has to pay for. Instead, this is an invitation to reassess the current interaction between relevant disciplines in the development of master plans in the Middle East.

We understand that convincing stakeholders that sustainability enhances long-term financial performance may be a challenge, especially if there is a perception that environmentally friendly practices are economically burdensome. We encourage all stakeholders to challenge the perceived conflict between environmental sustainability and profitability by adopting this framework as a standard way of practice. Our hope is that this becomes a standard way of planning our cities and does not necessitate to be dictated by the client.

Undoubtedly, as members of the industry and community we ultimately want to achieve resilient, healthy and sustainable communities for all.